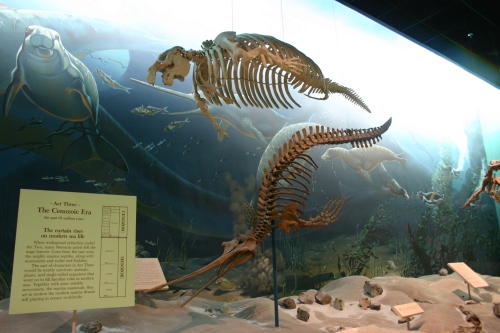

The very nature of whales precludes scientific study of these incredible animals. They are enormous—strong and powerful in life and unwieldy to manipulate in death. They live in the open ocean, where they can only be reached by boat or plane. Living whales fare poorly in captivity, and dead whales rapidly deteriorate into an oily, reeking mess. If there was ever a natural specimen that does not lend itself to display in a museum, it would be a whale.

This is not for lack of trying. Museums have long sought to collect whales, both to complete their records of biodiversity and to show the visiting public the spectacular extremes of animal life. Success in this endeavor has always been mixed. The Natural History Museum of London has one of the best collections of real whales, including dolphins, porpoises, and a humpback (Megaptera novaeangliae) fetus pickled in bathtub-sized vats of alcohol. Larger whales*, however, can only be displayed as skeletons, which unfortunately misrepresent the shape of the living animal (and as many museums have learned the hard way, even whale bones stink and drip blubber for years after cleaning). Many taxidermists have attempted to preserve the skins of large whales over the years, but this has typically resulted in grotesque, short-lived failures**.

A Smithsonian team takes plaster molds from a blue whale caught by whalers in Newfoundland. Source

A museum is a place for real things, but what can museum workers do if a specimen is so irreconcilable with the practicalities of display? Throughout the 20th century, many museums have experimented with life-sized model whales. Vouched by scientists and based on photographs and measurements of actual whales, these models provided (and continue to provide) many visitors with the closest experience they will ever have to seeing a giant whale in person. However, to display a model is to raise key questions about authenticity. Constructed from papier-mâché, plaster, or fiberglass, a model whale lacks the flesh-and-blood reality of a true whale. Its legitimacy comes from a disassociated set of observations, and the perceived authority and expertise of the scientists who made them. The situation is complicated by the fact that we know remarkably little about living whales, and historical scientists knew even less. Model whales have never been intended to deceive audiences, but many could hardly be called accurate reconstructions today.

In the 19th century, the only people who had seen living whales up close were whalers—a group probably more concerned with staying alive than making careful anatomical observations. Scientists had to rely on occasional, all-too-brief surface sightings and the misshapen corpses of beached animals. While the situation has improved, we still know precious little about whales’ lives below the waves. Is it scientifically acceptable, or even ethical, to present a reconstruction of an animal based on such limited information? Let the epistemological nightmare begin!

*By large whales, I am referring primarily to mysticetes and the sperm whale (Physter macrocephalus).

**One notable exception is the juvenile blue whale at the Göteborg Natural History Museum in Sweden. Not only is this the only mounted mysticete in the world, it is the only whale to have an upholstered seating area inside. Once a destination for lovers’ trysts, the whale’s interior now hosts Santa Claus at Christmastime.

Round 1: 1880 – 1938

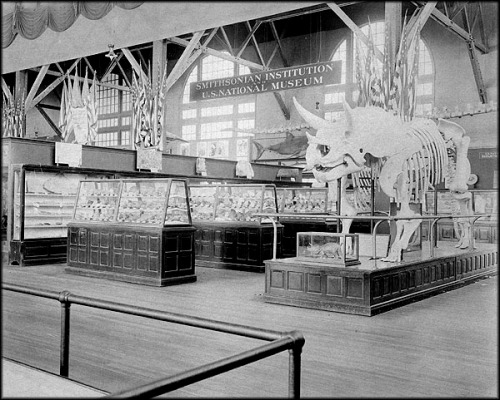

This bisected humpback at the United States National Museum was the first large whale replica displayed at a major museum. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Spencer Baird, the Smithsonian’s first curator, was a marine biologist with a strong interest in cetaceans. He quickly made the Smithsonian a place for whales, assembling an impressive collection and hiring staff with similar research priorities. It is therefore no surprise that the first full-sized replica of a large whale would be built at the United States National Museum. In 1882, exhibit specialist Joseph Palmer mounted the skeleton of a humpback whale with its left side enclosed in a plaster death cast of the same individual. This display lasted until the early 20th century, when it was scrapped during the move from the Arts and Industries Building to what is now the National Museum of Natural History. In 1901, Ward’s Natural Science Establishment provided a similar half-mount of a sperm whale to the Bishop Museum in Honolulu.

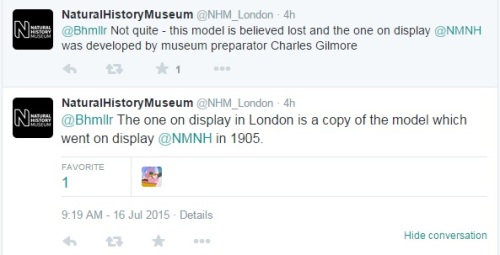

However, museum workers soon set their sights on bigger whales—specifically, the largest animal the Earth has ever known. In 1903, Smithsonian Curator of Mammals Frederick True teamed up with Head of Exhibits Frederick Lucas to create the first scientifically informed life-sized model of a blue whale (Balaenoptera musculus). To accomplish this, the two Fredericks traveled to the Cabot Steam Whaling Company processing station in Newfoundland. At this point in time, whaling had progressed well beyond the rickety wooden ships described by Melville. It was a technologically sophisticated and ruthlessly efficient operation, largely conducted from floating meat factories armed with explosive harpoons. This period of industrialized whaling drove many whale species to the brink of extinction. For their part, True and Lucas were convinced that they only had a few years left to observe a giant cetacean firsthand.

After debuting at the St. Louis World’s fair, Lucas’s blue (or “sulphur-bottom”) whale found at home at USNM. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives..

True and Lucas watched the whalers haul in several smaller blue whales before selecting a 78-foot, 70-ton behemoth as their subject. Once the whalers brought the dead animal into shallow water, the museum workers rode out in a dinghy to measure the whale and take plaster molds of its flank, flukes, and head. They worked continuously over two days, racing to beat the onset of decomposition. The resulting molds only represented half the animal, and were significantly distorted by the sagging and bloating of the carcass, but Lucas made do.

Following Carl Akeley’s general method for creating life-like taxidermy mounts, Lucas started by blocking out the whale’s basic dimensions with a steel and basswood frame. His team then used wood and wire mesh to further shape the boat-like model, and finished it with an outer layer of papier-mâché. It is unclear if Lucas was able to use any actual casts of the Newfoundland whale, or if he sculpted it freehand using the molds as reference. Most likely, it was a combination of the two. The colossal model was shipped by rail for its debut at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis (alongside a familiar Stegosaurus and Triceratops). Afterward, Lucas’s whale was displayed in the Arts and Industries Building, and later, in the west wing of the newly completed NMNH.

In 1906, the American Museum of Natural History started work on a blue whale of their own. Rather than measuring their own dead whale, the AMNH exhibits team led by F.C.A. Richardson (who also built the NMNH Stegosaurus) used measurements from True’s monograph, Whalebone Whales of the Western North Atlantic. In fact, the New York model ended up with virtually identical proportions to its Smithsonian predecessor, and was probably styled after the same Newfoundland carcass. Richardson ran into trouble when he couldn’t get his whale’s papier-mâché skin to hold up—it sagged against the wooden frame, making the model look emaciated. Richardson was eventually dismissed from the project, replaced by Roy Chapman Andrews (who would later lead the Central Asiatic Expeditions). At the time, neither Andrews nor anyone else working on the model had ever seen a whale in person. Still, the completed model was, by all contemporary accounts, just as convincing as the Smithsonian version.

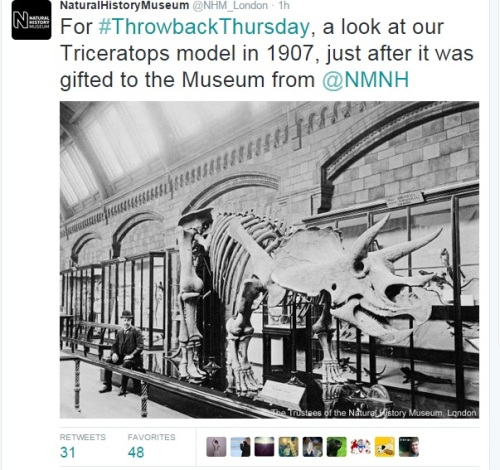

It seems there is nowhere in the NHM Hall of Mammals where one can see, much less photograph, the entire blue whale. Source

On the other side of the Atlantic, London NHM scientists scoffed at the Americans and their replica whales. Zoological Department head William Calman was particularly contemptuous, opining that natural history museums should only display real specimens. Apparently something changed in the decades that followed, because in 1937 NHM unveiled a wood-and-plaster blue whale model built by Percy Stammwitz. For some reason it is often claimed that the London cetacean was the first life-sized blue whale replica, which is plainly untrue. Nevertheless, at 92 feet and seven tons, it was the largest such exhibit when it debuted. It is also the oldest blue whale replica that is still on display today.

Round 2: 1963 – 1969

The Smithsonian’s second blue whale model dominated the Life in the Sea exhibit. Photo courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Back in America, the NMNH and AMNH blue whales endured for several decades. Eventually, however, new cetacean research and new standards for museum displays made these first generation models obsolete. In the late 1950s, Frank Taylor initiated the Smithsonian-wide modernization program, which was to replace the institution’s aging exhibits. Early on the agenda was an update to the marine life exhibit, home to the 1904 blue whale. Designing the new hall was like pulling teeth, as intransigent curators refused to cooperate or furnish specimens for what they saw as a misguided endeavor*. Still, Taylor was able to commission a new, larger blue whale model to serve as the exhibit’s centerpiece.

The first NMNH whale bore an unfortunate resemblance to a giant grey sausage**. True and Lucas based the proportions on a bloated and decomposing carcass, understandably missing some of the nuances of the animal’s form. Meanwhile, the model’s stiff posture and cylindrical shape were necessary given the structural limitations of the materials used in its construction. The 1963 model corrected both problems. Although photographs of living blue whales underwater were still a decade away, footage of grey whales (Eschrichtius robustus) at sea helped the model-makers imbue their creation with life. The model was given a gentle diving pose, and lightweight plastic and fiberglass helped make this more dynamic sculpture possible. With a total length of 94 feet, the new whale was painted a cheery light blue, with pale yellow spots. Two steel beams secured the model’s left side to the north wall of the gallery.

After several false starts, AMNH began serious work on a replacement for their own outdated sausage-whale in 1967. The new blue whale model would be the centerpiece of the long-delayed Hall of Ocean Life, now slated to open for the museum’s centennial in 1969. This firm deadline made an already challenging project even more stressful—by the end, Department of Mammology Chair Richard van Gelder had threatened to resign twice, and was nearly fired three times.

The rig securing this 9-ton blue whale model to the ceiling is an engineering marvel. Photo courtesy of the AMNH Research Library.

To start, van Gelder was frustrated by the museum administrators’ firm insistence that the new whale not be suspended by wires (which they thought looked tacky). As a tongue-in-cheek counter-proposal, van Gelder suggested the museum construct a dead, beached whale splayed out on the floor. To his chagrin, the administrators loved the idea because it would be much cheaper. Gordon Reekie of the exhibits department began planning an immersive experience with the sounds of gulls and crashing surf. As legend has it, van Gelder successfully sabotaged the dead whale concept when he told a group of donors that the smell of the rotting carcass would also be simulated.

Lyle Barton eventually devised the final plan, in which the steel structure securing the whale to the ceiling would be hidden within the model’s arching back. Once van Gelder deflected a last-minute request to give the whale an open mouth (not only was this inaccurate, but it would tempt people to throw things into it), workers from StructoFab carved the model from huge blocks of polyurethane. Like Andrews before him, van Gelder had never seen a blue whale in person, but did his best to ensure the accuracy of the model—down to the 28 hairs on its chin.

One more headache remained: at nine tons, the completed model was heavier than anticipated. 600 pounds of paint had to be sanded off and reapplied with a lighter touch before the model met the recommendations of two independent teams of engineers. Still, Barton insisted on measuring the distance between the whale’s chin and the floor every day for several months, just in case.

“The Squid and the Whale” with its original paint job. Source

In addition to the blue whale, the Hall of Ocean Life debuted with a second model cetacean. This famous diorama depicts the head of a sperm whale as the animal wrestles with a giant squid (Architeuthis dux). When the model was built, nobody had ever seen a live giant squid, much less one battling the world’s largest predator. We know that sperm whales eat squid because squid parts are found in their bellies. Suction-cup scars on whales’ faces tell us the squid do not always do down without a fight. Still, the 1960s modelmakers had to guess at the appearance of the cephalopod. Even the sperm whale proved difficult to recreate: these animals appear light grey underwater but almost black on the surface, and curators argued how to paint the model. This was rendered moot when the diorama was placed in a nearly pitch-black environment, simulating the gloomy depths 23,000 feet under the sea. Barely visible in the darkness, this display is fantastically eerie. The fact that the event it represents has never been (and may never be) witnessed by human eyes makes it all the more unsettling.

*Curators objected to the planned exhibit’s interdisciplinary presentation, which would use specimens to make broader points about ecology, climate, and maritime history. They preferred displays that were divided by sub-discipline and which strictly adhered to taxonomic tradition.

**Counterintuitively, the awkward, stiff shape of the original NMNH blue whale actually made it more believable: many visitors thought they were looking at a real taxidermied whale gone slightly awry. One of the aims when designing a replacement was to reduce confusion by creating an object that was clearly artificial.

Round 3: 2003 – Present

The restored AMNH blue whale in 2015. Photo by the author.

Sadly, not all of the historic cetacean models are still with us. The original NMNH blue whale was discarded in the early 1960s to make way for its replacement. AMNH saved its first whale in storage until 1973, when they offered it free of charge to anyone who could arrange for its removal from the building. When no serious offers were made, this model was also demolished (although the eyeball was sold during a fundraising event). The second NMNH blue whale eventually proved to be somewhat inaccurate: the throat was over-inflated and the coloration was all wrong. It was hidden from view for most of the 1990s, although its back was still visible over a blockade. In 2000, the west wing was converted into the Mammals Hall, and the construction contractor gained ownership of the unwanted whale. He briefly listed the model on eBay, but unfortunately the whale fell apart once it was pulled off the wall.

The International Whaling Commission banned the hunting of blue whales in 1966. Since that time, interest in conservation and improved technology have enhanced our understanding of these marine giants. While few blue whale behaviors have been observed, much less photographed, marine biologists know far more than they did half a century ago. Armed with better knowledge of blue whale anatomy, AMNH exhibits staff made several modifications to the 1969 model. In addition to a resculpted jawline and a relocated blowhole, the whale gained a navel and an anus (both details were overlooked the first time around). Finally, its slate gray skin, based on photographs of beached carcasses, was repainted in the vivid blue of a living whale.

Like the blue whale, the AMNH giant squid was remodeled and repainted in 2003 based on new information about this elusive creature’s shape and color. Photo by the author.

The roster of model cetaceans has seen several additions in recent decades. Among them are a gray whale built for the Monterey Bay Aquarium in 1984, and yet another blue whale displayed outside Tokyo’s National Museum of Nature and Science. One of the newest life-sized whale sculptures to grace museum halls is Phoenix, a North Atlantic right whale (Eubalaena glacialis) on display at NMNH since 2008. This model is special because it represents a real, individual animal that is alive in the ocean today.

Scientists at the New England Aquarium have tracked the real Phoenix (a.k.a. #1705) since her birth in 1987. She was selected for the NMNH model because her life history is well known, and because the ongoing study of this individual presents an opportunity to show science in action. An interdisciplinary group of researchers including Marilyn Marx, Amy Knowlton, Michael Moore, Jim Mead, and Charles Potter spent two years working out every detail of the model, down to the chin scars Phoenix got in a run-in with a fishing net. Missouri-based Elemoose Studios was commissioned to build the full-sized model. Because the historic space the whale was to be exhibited in could not support the weight of a traditional fiberglass model, modelmaker Terry Chase had to get creative. He designed an ultra-light aluminum frame, with a foam build-up and paper skin. The completed model is 45 feet long but weighs only 2,300 pounds.

Phoenix floats majestically in the NMNH Ocean Hall. Source

A model whale will always be an imperfect substitute for reality. Early attempts were limited as much by available technology and materials as they were by an incomplete understanding of their living counterparts. Lucas and Andrews could scarcely dream of the light but strong urethane foam used to create the Phoenix replica. Nevertheless, model whales have become steadily more accurate with each generation, keeping pace with marine biologists’ improving access to whales in their natural habitat. With considerable effort, it is now even possible to exhibit a convincing duplicate of a living individual.

The advantage of a model whale is that it is much easier to observe than a real whale. Paradoxically, this is also what makes these exhibits so epistemologically challenging. Even for somebody fortunate enough to have seen a whale at sea, a museum model is a much more visceral and relatable encounter. Almost nobody has seen a living blue whale underwater, but millions see the AMNH model every year. For those people, this chunk of polyurethane IS a blue whale. It represents their understanding of the animal, and is how they make sense of any fleeting glimpses of real whales they may have seen. Creating a whale stand-in is therefore not only technically challenging for a museum, it is an immense responsibility.

References

Burnett, D.G. 2012. The Sounding of the Whale: Science and Cetaceans in the Twentieth Century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hoare, P. 2010. The Whale: In Search of the Giants of the Sea. New York, NY: HarperCollins.

Quinn, S.C. 2006. Windows on Nature: The Great Habitat Dioramas of the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: Abrams.

Rader, K.A. and Cain, V.E.M. 2014. Life on Display: Revolutionizing U.S. Museums of Science and Natural History in the Twentieth Century. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Rossi, M. 2008. Modeling the Unknown: How to Make a Perfect Whale. Endeavour 32: 2: 58-63.

Rossi, M. 2010. Fabricating Authenticity: Modeling a Whale at the American Museum of Natural History, 1906-1974. Isis 101: 2: 338-361.

Smithsonian Institution. 2008. Modeling Phoenix, Our North Atlantic Right Whale. http://naturalhistory.si.edu/exhibits/ocean_hall/whale_model.html

Smithsonian Institution. 2010. A Century of Whales at the Smithsonian Institution. http://naturalhistory.si.edu/onehundredyears/profiles/Whales_SI.html

Wallace, J.E. 2000. A Gathering of Wonders: Behind the Scenes at the American Museum of Natural History. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

I’ve never written a book review here before, but Karen A. Rader and Victoria E.M. Cain’s Life on Display: Revolutionizing U.S. Museums of Science and Natural History in the 20th Century is a fine place to start. Published in 2014, this fascinating and exhaustively researched volume follows the struggle of natural history museum workers to define the purpose of their institutions. Ultimately, are museums places for exhibits, or places for collections? Rader and Cain chart the internal and external perceptions of natural history museums through time, recounting the people and events that made these institutions what they are. If you have a serious interest in science communication or the history and philosophy of science, Life on Display is a must-read.

I’ve never written a book review here before, but Karen A. Rader and Victoria E.M. Cain’s Life on Display: Revolutionizing U.S. Museums of Science and Natural History in the 20th Century is a fine place to start. Published in 2014, this fascinating and exhaustively researched volume follows the struggle of natural history museum workers to define the purpose of their institutions. Ultimately, are museums places for exhibits, or places for collections? Rader and Cain chart the internal and external perceptions of natural history museums through time, recounting the people and events that made these institutions what they are. If you have a serious interest in science communication or the history and philosophy of science, Life on Display is a must-read.