“No progress at all. Rhinos too thick.”

So wrote American Museum of Natural History fossil collector Albert Thomson in his September 1917 field notes. At that point, Thomson been collecting mammal fossils at Agate Springs nearly every year since 1907—and was still finding rhino bones in such abundance that they formed a seemingly impenetrable layer.

Located in northwest Nebraska and dating to about 22 million years ago, the Agate Springs bone bed is an aggregation of fossilized animals on an astonishing scale. Like the Carnegie quarry at Dinosaur National Monument, it provides a snapshot of an ecosystem at a moment in geologic time. But while a high estimate of the individual dinosaurs represented at Carnegie Quarry is in the hundreds, the main bone bed at Agate Springs may well contain tens of thousands of animals. The vast majority of fossils come from the tapir-sized rhino Menoceras, scrambled and packed together in a layer up to two feet thick. Moropus, Daeodon, and an assortment of other hoofed animals and small carnivores have also been found. These animals may have gathered during a drought and succumbed to thirst or disease, before the returning rains rapidly buried their remains. It’s also possible that the bone bed represents a mass drowning during a flash food. Since different parts of the site vary in density, Agate Springs likely represents multiple mortality events over a number of years.

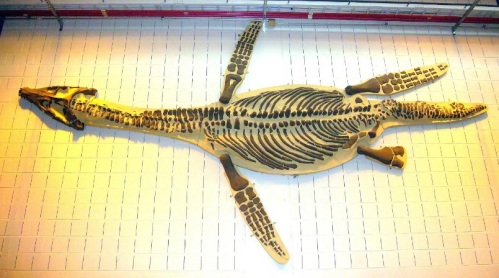

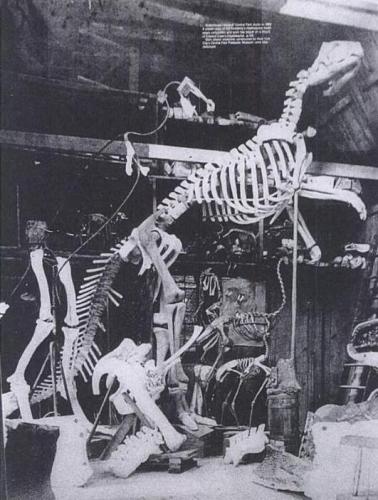

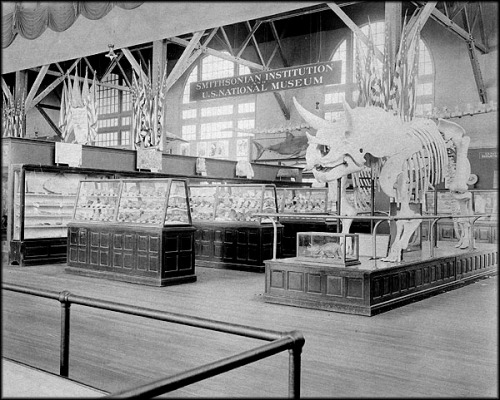

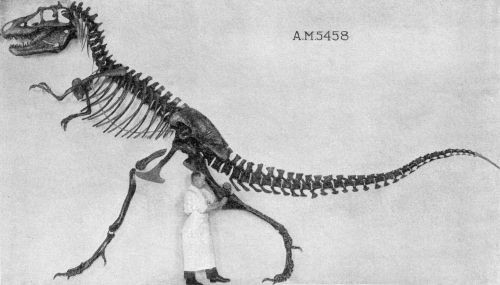

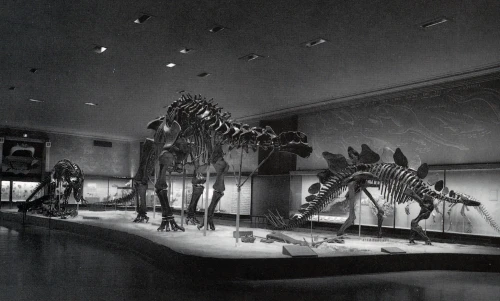

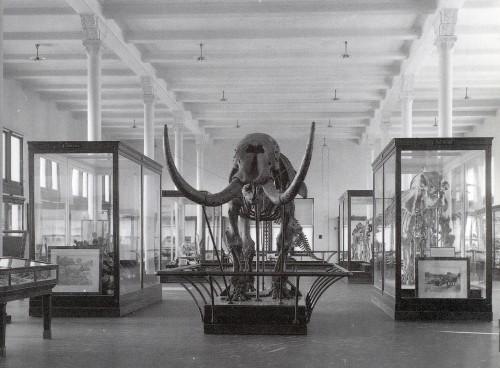

Tableau of cast fossil skeletons at the Agate Fossil Beds National Monument visitor center. Photo by the author.

Today, less than 30% of the Agate Springs bone bed has been excavated, but not for a lack of effort. Teams from a half dozen museums visited the site between 1900 and 1925, with the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CM), the University of Nebraska State Museum (UNSM), and the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) establishing large-scale excavations and returning year after year. As we shall see, the relationships between these teams were not always amicable, making this period at Agate Springs a window into the preoccupations of museum workers at the turn of the century. Agate Springs also illustrates how east coast paleontologists interacted with and relied on local people, defending their social capital as jealously as any fossil deposit. Finally, museums’ interest in Agate Springs in the mid 20th century exemplifies how exhibitions had evolved during the intervening period.

The setting

Agate Springs is unceded Sioux territory, occupied by settlers after the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. James Cook purchased the treeless tract of rolling hills from his father-in-law in 1887, naming it Agate Springs after the rocky banks of the nearby Niobrara River. James and Kate Cook established a ranch where they raised horses and cattle, and Agate Springs became a popular stop for travelers on their way to Cheyenne, Wyoming.

The Cooks were aware of bones weathering out of the hills as far back as 1885, when the land was still owned by Kate’s father. James knew that scientists were on the lookout for fossils in the region—by one account he worked for O.C. Marsh as a translator in 1874. Once the ranch was established, he began writing to museums, including UNSM in Lincoln and the Carnegie Museum in Pittsburgh, inviting them to visit Agate Springs. A UNSM party led by Erwin Barbour was the first to drop by, spending a night at the Cook homestead in July 1892. Chiefly concerned with collecting “devil’s corkscrews” (ancient beaver burrows) north of the Niobrara, Barbour sent his student F.C. Kenyon to check out the bones Cook promised in the nearby hills. Kenyon collected as much as he could carry, but his report apparently did not excite Barbour, and the UNSM party moved on.

It would be twelve years before another paleontologist visited Agate Springs. Olaf Peterson of the Carnegie Museum stopped by the ranch in early August of 1904, at the end of a tumultuous field season in western Nebraska. Peterson had received a telegram on July 4 that his brother-in-law, boss, and mentor John Bell Hatcher had died of typhoid. Peterson intended to cut the season short, but Carnegie Museum director William Holland denied the request, writing in no uncertain terms that Peterson was to continue his work in Nebraska. Later in July, Peterson fell ill himself, and spent several days recovering in Fort Robinson. Suffice it to say, Peterson was not in the best of moods when he arrived at Agate Springs.

Nevertheless, the outcrops Peterson saw at Agate Springs revitalized his spirit. Accounts differ on what part of the site Cook showed him (this will be important shortly), but when he returned east two weeks later he was raving about a quarry with “ten skulls within a six-foot radius.” In Pittsburgh, Peterson and Holland began drawing up plans for an ambitious excavation the following year. In their view, they had staked a claim to the site: just like contemporary gold and oil prospectors, turn-of-the-century paleontologists lived by the rule of “dibs.” For the museum crowd, being the first scientist to “discover” a quarry meant an entitlement to control the site and the resources it produced. This included both the physical fossils and the privilege to describe and interpret those fossils—controlling the site meant controlling scientific knowledge.

Dueling quarries

Cook either didn’t know about such customs, or didn’t care. To his credit, Cook was never interested in monetizing the fossils at Agate Springs. By all accounts, he simply wanted to share with the world the knowledge that the bone bed represented. He was concerned that it was so expansive that no single team could uncover all its secrets. On May 26, 1905, Cook wrote to Barbour, inviting him to share in the bounty he had shown Peterson the previous summer, explaining that it was “so large that [the Carnegie team] could not work it out in years, so there is plenty of material for other parties to work with.”

On other occasions, Barbour had taken a cautious stance when corresponding with landowners. In this case, however, he could barely contain the enthusiasm in his reply. In a single letter, Barbour reminded Cook that UNSM had visited 12 years before and therefore should have collecting rights, asked Cook to place a literal flag on the site claiming it for the University of Nebraska, offered to hire Cook’s 18 year-old son Harold as a field assistant, and appealed to Cook’s state pride by listing the out-of-state institutions that were removing Nebraska’s fossil heritage each year.

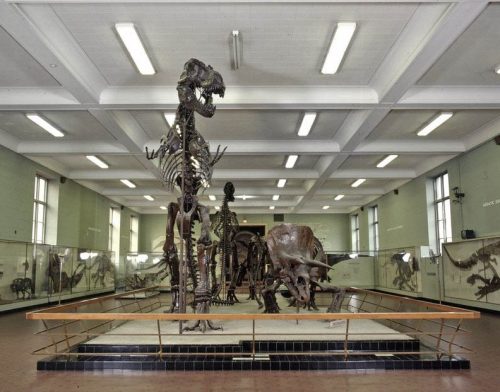

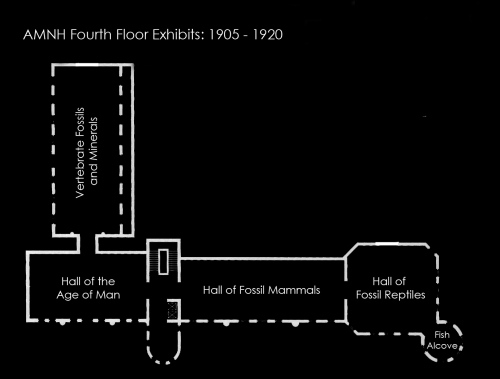

Carnegie Hill and University Hill today. Photo by the author.

That summer, Peterson and Barbour opened quarries on two neighboring buttes at Agate Springs, which came to be known as Carnegie Hill and University Hill. While the two parties were cordial neighbors, letters exchanged by Holland, Barbour, and Cook demonstrate that the museum directors were uncomfortable with the situation. Holland repeatedly wrote to Cook, claiming that his team was more skilled than Barbour’s and warning that it would be bad for science if the fossils and geological data were split between two institutions. Harold Cook didn’t appreciate Holland’s condescending tone. In a note to his father pinned to one of the letters, he wrote that “a letter of this kind is the work of a pinheaded, egotistical, educated fool.”

The Carnegie and UNSM teams returned to Agate Springs in 1906, but spent the summer of 1907 elsewhere. The elder Cook took the opportunity to invite yet more paleontologists, and teams from AMNH, the Yale Peabody Museum, and Amherst College showed up to collect fossils.

Meanwhile, Holland began a campaign to wrest control of the site by any means necessary. He became particularly focused on the narrative of who discovered the bone bed. According to Holland, Cook had shown Peterson the smaller, less dense site that would be come to be known as Quarry A. Peterson then went prospecting on his own and found the primary bone bed that straddled the two buttes. Holland went on to argue that regardless of who first saw the fossils, Peterson earned credit for the discovery because he was the first trained scientist on the scene, and therefore the first individual to correctly identify the age and identity of the animal remains.

Cook rejected Holland’s retelling of the events of August 1904, insisting that he had known of the bone bed for years before he showed it to Peterson. In many ways, the two men were talking past each other. Cook found Holland’s insistence on claiming the discovery for Peterson nonsensical and disrespectful—he knew his own land, and he was the one who invited the paleontologists in the first place. Holland, on the other hand, was staking a claim among his fellow academics. He needed to demonstrate that the Carnegie Museum had been at Agate Springs first, so that other institutions would yield to his authority to interpret and publish on the fossils.

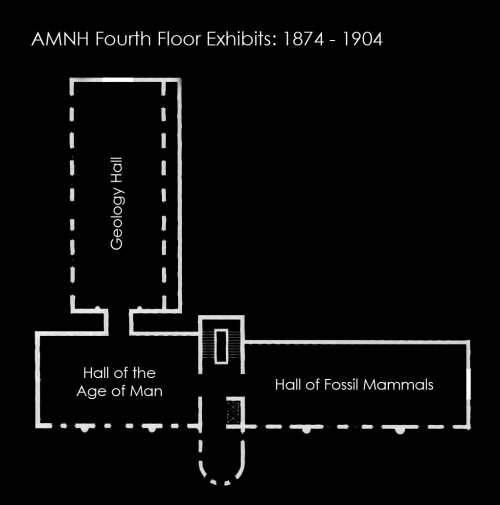

Harold Cook’s homestead cabin, recently fixed up and painted. Photo by the author.

Late in 1907, Holland visited the Cooks’ ranch in person for the first time. He offered to buy the fossil-bearing land outright, doubtlessly planning to block the other museums from accessing it. At this point, James Cook made the awkward discovery that Carnegie Hill and University Hill were actually just outside his official holdings, in the public domain. Holland moved to purchase the land, but Harold Cook beat him to it, building a cabin and filing a homestead claim in March 1908. In their gentlemanly rancher way, the Cooks told Holland to get lost, and the Carnegie Museum left Agate Springs for good.

Playing nice

While Holland had managed to sour his relationship with a remarkably welcoming and accommodating landowner, Barbour did the opposite. In letters to Cook, he regularly acknowledged the rancher as the discoverer of the site. He visited the Cooks frequently and employed Harold in the UNSM quarry, training the younger Cook into a formidable fossil prospector and anatomist. Soon Harold was studying at the University of Nebraska under Barbour, and a few years later, Harold and Barbour’s daughter Elinor were married. Barbour also named a few species after the Cooks, including Moropus cooki.

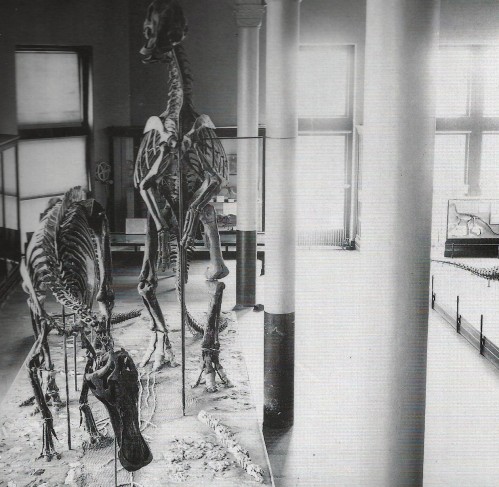

AMNH director Henry Osborn and field manager Albert Thomson had a similarly positive relationship with the Cooks. The New York museum took over Carnegie Quarry in 1908, and Osborn visited several times to express his gratitude. Like Barbour, he paid Harold for his time, labor, and expertise. Later, Osborn invited Harold to work at AMNH during the off-season. In return, AMNH was permitted to collect at Agate Springs for nearly two decades. Thomson returned almost every year through 1923, and the museum accumulated so many Menoceras and Moropus fossils that it began selling and trading them to other institutions.

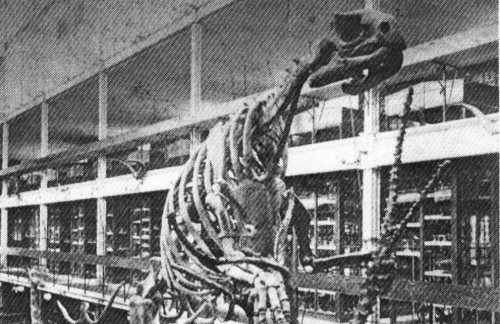

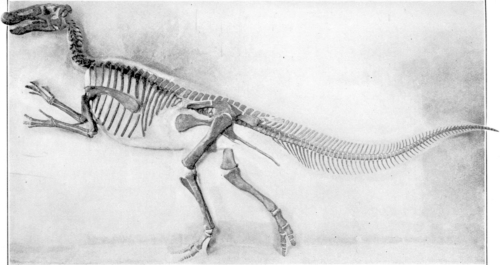

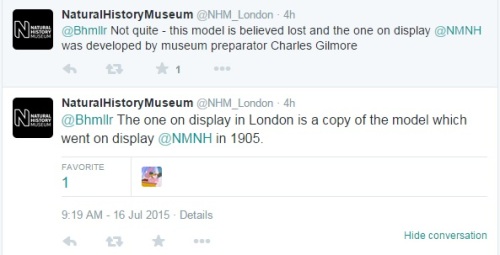

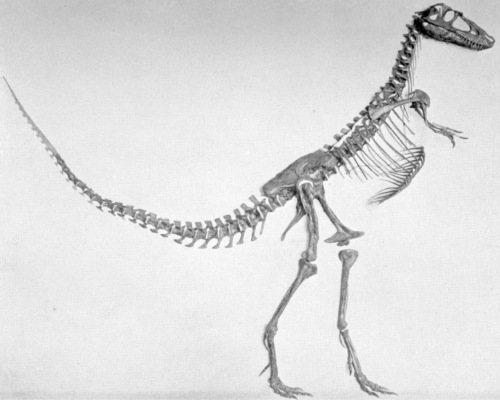

Menoceras and Moropus slab at the National Museum of Natural History. Photo by the author.

The reward for staying in the Cooks’ good graces was clear. UNSM and AMNH paleontologists gained access to the Agate Spring quarries for many years, accumulating large collections. They earned accolades from publications, public interest from the skeletons they placed on exhibit, and even monetary rewards from selling the excess specimens. Meanwhile, the Carnegie Museum was shut out after their first few seasons of collecting because Holland was, if not outright hostile to the Cooks, unable to communicate effectively with the ranchers. For American paleontologists at the turn of the century, social capital was a critical resource. Positive relationships with landowners and other individuals in the fossil-rich western states earned them access to land, information about the terrain, and networks of eyes on the ground, any of which might lead them to the next important quarry.

You get a rhino block, and you get a rhino block…

The scale and intensity of the Agate Springs excavations decreased after 1910, and in the early 20s, Thompson and the AMNH crew closed up shop, believing they had found examples of every species that could be found. By that time, the site’s value for museums had shifted. Rather than being a bonanza of specimens to collect, categorize, and publish on, Agate Springs had become a place to quickly and easily obtain display-worthy fossils. As Hunt puts it, the site was a “storehouse of good exhibit materials, to be tapped when needed by museums wishing to mount a rhino or two.”

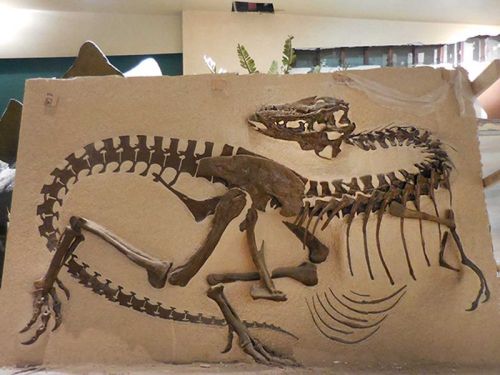

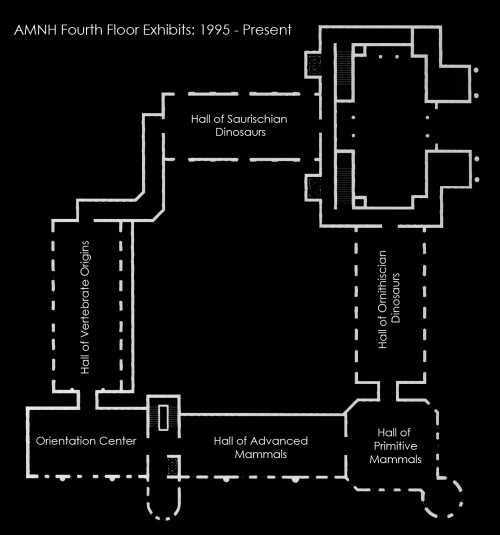

Today, Agate Springs fossils—acquired in the field or via trade—are on display at large and small museums all over North America. Many of these are mounted skeletons of rhinos, camels, and Moropus, but there is also a particular abundance of large, incompletely prepared slabs, which provide viewers with a small window into the Agate Springs bone bed. Because of the sheer density of bones, the early 20th century excavation teams quickly stopped jacketing fossils individually, and instead began preparing out large blocks, typically four to six feet across. The blocks were hardened with shellac, and reinforced with wood planks around their borders. Pulleys and cranes were required to lift the largest blocks out of the quarries. In the early years, the intention was to fully excavate these blocks at their respective museums. It’s not clear which museum first placed a complete block on exhibit, but the idea proved popular. Many later visitors to Agate Springs, from James Gidley of the National Museum of Natural History in 1909 to Elmer Riggs of the Field Museum of Natural History in 1940, came with the express purpose of collecting intact slabs for display.

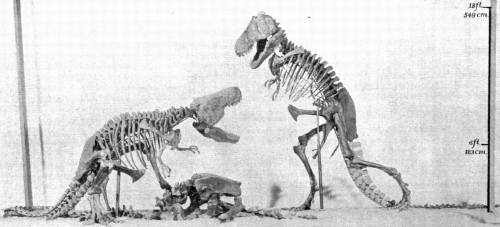

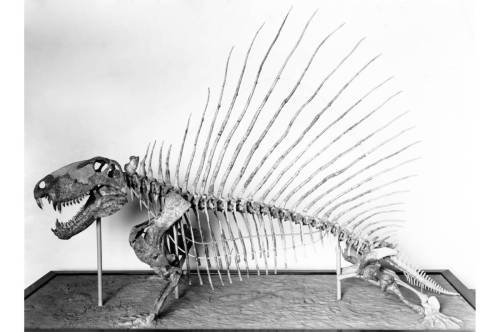

Menoceras slab on display at the Field Museum of Natural History. Photo by the author.

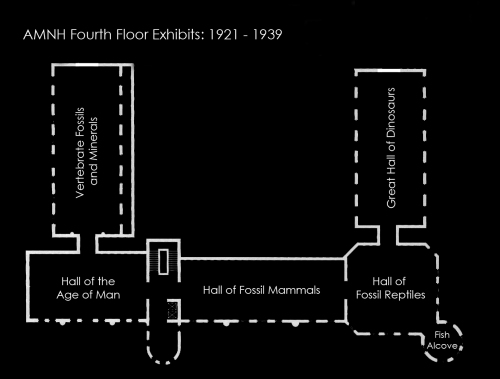

The popularity of fossil blocks from Agate Springs coincides with a shift in philosophy toward exhibitions at natural history museums. While early 20th century exhibits were catalogs of life, emphasizing the breadth of the museum’s collection, by the 1920s and 30s many museums had begun moving toward narrative exhibits. Displays were intended to communicate ideas, and objects served as illustrations of those ideas. The fossil blocks from Agate Springs were ready-made illustrations of a number of paleontology concepts, from the process of taphonomy to the task of excavation millions of years later. Most have remained on display to this day, a fact that James Cook would undoubtably be pleased with.

An incomplete list of museums in possession of Agate Springs blocks follows. Do you know of others? Please leave a comment!

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History

- American Museum of Natural History

- University of Nebraska State Museum

- Field Museum of Natural History

- National Museum of Natural History

- Royal Ontario Museum

- Denver Museum of Nature and Science

- Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History

- Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology

- University of Wyoming Geological Museum

- South Dakota School of Mines and Technology

- Wesleyan University Geology Museum

- University of Austin Texas Memorial Museum

- University of Michigan Museum of Natural History

- Science Museum of Minnesota

- Fort Robinson State Park Trailside Museum

References

Agate Fossil Beds: Official National Park Handbook. Washington, DC: National Park Service.

Hunt, R.M. 1984. The Agate Hills: History of Paleontological Excavations, 1904-1925.

Vetter, J. 2008. Cowboys, Scientists, and Fossils: The Field Site and Local Collaboration in the American West. Isis 99:2:273-303.

Skinner, M.F., Skinner, S.M., Gooris, R.J. 1977. Stratigraphy and Biostratigraphy of Late Cenozoic Deposits in Central Sioux County, Western Nebraska. Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History 158:5:265-370.